The phrase “Orbital Data Centers” has exploded into the lexicon over the last six months. What was a fringe idea a year ago has now been embraced by the likes of Google and SpaceX. Much ink has been spilled debating the merits: Is it technically feasible? Does it make economic sense? Is it a shortcut around power, water, and permitting constraints? Who’s best positioned to win this new trillion-dollar space race?

All reasonable questions — and all missing the point.

The real story is that we are deep in the throes of a space technology revolution as transformative as the information technology revolution a generation ago.

The implications extend far beyond datacenters —

- The boundary between space and Earth infrastructure will dissolve into integrated global infrastructure

- Every organization, public & private, will depend on space whether they intend to or not

- The synthesis will create massive opportunities but also new risks and unknowns

The value to be unlocked is huge but the dynamics are not obvious to most. How this unfolds and who wins will reshape economies and determine the global balance of power over the next 20 years.

Will there be datacenters in space? Yes, it is inevitable. But that’s only part of a much bigger transformation.

Gravity Well

In the summer of 2004, I was offered an internship with an unlikely startup. Surrounded by cows grazing the flat Texas grassland as far as the eye could see, my job was to help develop pieces of a commercial orbital rocket — an endeavor anyone with a brain assumed was doomed to failure.

“Intern,” I was commanded in my first week on the job, “come help me put together Merlin.” And so, sitting in a poorly lit blockhouse partially underground in the Bible Belt of Texas, I helped Jeremy Hollman assemble the first-ever integrated first stage engine for SpaceX.

Two days later that engine tore itself apart in a ball of flames on Vertical Test Stand 1. The ensuing fire burned most everything useful out of the test stand. My job the rest of the summer: lie upside down in the scalding mid-summer Texas heat and rewire VTS-1.

An inauspicious start. At that time there were about 50 employees at Elon Musk’s Space Exploration Technologies. It would take SpaceX another four years, three failed launches, and a lot of personal grit and money to “make orbit” with a sub-scale, inefficient, and not terribly practical Falcon 1 rocket in 2008.

A year after SpaceX first made it to orbit, I was approached by four friends from Stanford about joining a startup they’d founded called Skybox Imaging. The idea was simple: leverage the same revolution in integrated, low-power computing, radios, and sensors that had made the iPhone possible to build much smaller imaging satellites than had previously been possible.

“SpaceX is solving the launch problem,” we imagined, “we will flood the sky with smallsats.”

With unit economics 10–100x lower than the rest of the space industry, we would launch dozens of them and “democratize” frequently updated, high-resolution overhead imagery.

Our belief in 2009 was that accessible launch was the unlock for commercial space. SpaceX’s success with Falcon 1 had ushered in a bright new era of space access that would remove launch as a barrier.

Not quite.

In 2010, SpaceX announced that the Falcon 1 was not a viable business. All future flights would be cancelled — including two Skybox was a Gwynne-signature away from acquiring — and all resources would focus on the much larger Falcon 9 targeting the traditional market of school-bus-sized satellites.

So in 2013 I found myself traveling, for the second time, to a strategic missile base in southern Russia to integrate SkySat-1 onto a converted Russian SS-18 ICBM. Fearing for my life aboard a ‘60s-era Soviet jet and for my health alongside the world’s largest open-pit asbestos mine on the road to Yasny, I wondered how we had gotten here — two years late to launch, running out of money, totally dependent on a flimsy agreement with Russian oligarchs to get us into space.

Sketchy as it was, the SS-18 ICBM-based Dnepr rocket got SkySat-1 to space (with frightening accuracy). The satellite worked marvelously, and Skybox ultimately succeeded by many measures — we built 21 high-resolution satellites, most of which are still operating a decade later. Google acquired us for $500M in 2014. The first VC-backed satellite company also had the first big exit.

But the vision we had — thousands of satellites operated by a vibrant commercial sector deeply integrated with the world’s technology stack — remained unrealized. Launch remained a critical barrier preventing adoption and scaling.

It was too early.

Flywheels

Intel’s introduction of the 4004 microprocessor in 1971 made computing accessible and lit a technology fire that has burned for half a century. The microprocessor kicked off “Moore’s Law” — a self-reinforcing cycle of technical and economic innovation that has transformed the world.

From the Rube Goldberg launch days of Skybox, fast forward to today.

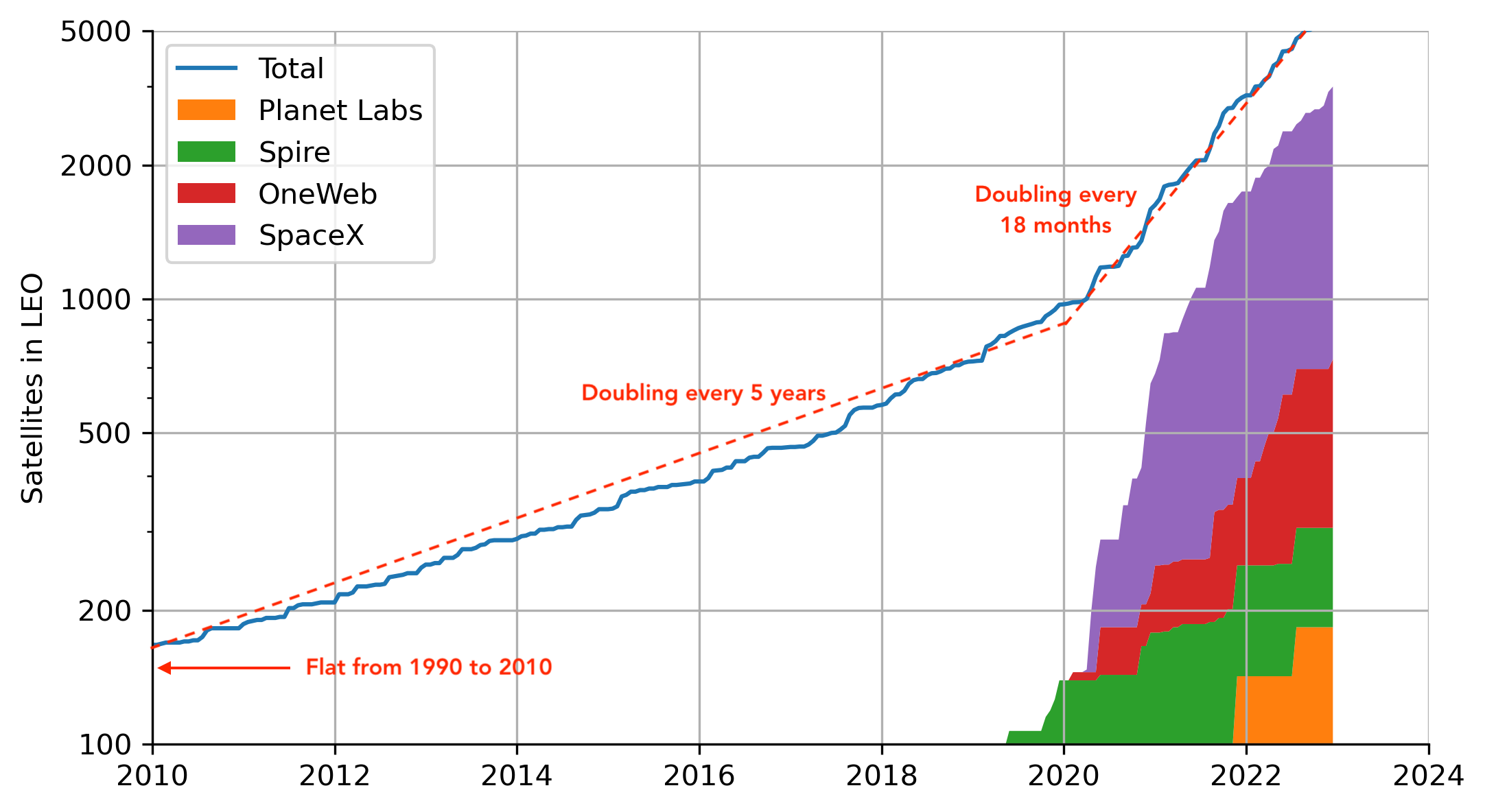

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 has become a workhorse unlike anything the world has seen. In 2025 alone it launched 165 times—compare that to 78 total launches from every country in the world in 2013. The cost to launch a SkySat-class spacecraft is now 10x less than aboard that repurposed Russian ICBM. After staying flat for half a century, since 2019 the number of satellites in orbit has doubled approximately every 18 months.

Thanks to SpaceX, we are at a Moore’s Law-like inflection point in space.

The economics that make this transformation possible are self-reinforcing in ways that most pundits haven’t articulated.

Launch cost and availability drives the economics of every space project. SpaceX has already reduced the cost per kilogram to orbit by roughly 2–5x. This didn’t happen due to a single fundamental technology breakthrough — instead SpaceX made two structural innovations that built a flywheel driving supply up and cost down.

Reuse

Before Falcon 9, no orbital rocket had significant reusability. Imagine commercial airlines buying a 737, flying it once cross-country and then throwing it away. The fixed costs would make commercial air travel unaffordable.

The Space Shuttle and sub-orbital testbeds like the DC-X had demonstrated limited reuse, but SpaceX was the first to achieve airline-like reusability on an orbital booster (and the upper stage fairing, an equally important factor often ignored). The advantage of amortizing the booster build over tens of flights has had a dramatic and structural impact on the economics of Falcon 9 launch (see launch cost calculator below).

Starlink

The second development is less obvious. Historically the fixed costs of a launch system dominate all variable costs. Launch base infrastructure and the “standing army” of engineering and operations personnel amortized over a small number (often 10 or less) launches per year rival or exceed the cost of the hardware itself.

SpaceX has now launched thousands of Starlink satellites. By creating captive demand for thousands of launches, SpaceX built a flywheel — Starlink drives launch cadence, cadence drives utilization, and utilization drives down marginal costs for everyone.

By attacking the high fixed-cost problem from two directions — reuse and Starlink-driven launch cadence — SpaceX completely disrupted the launch cost equation. See the interactive launch cost calculator below.

This feedback loop is about to accelerate. Starship’s full reuse and 6x larger payload capacity could reduce launch costs by another order of magnitude. At those prices the economics of space-based infrastructure change categorically.

We are approaching a tipping point where underlying factors like launch cost and deployed space infrastructure have evolved to a point of self-reinforcing transformation.

The Compute Crunch

The timing of this space revolution coincides with an unprecedented crisis in terrestrial computing infrastructure. The scaling laws that power transformer-based AI models have created insatiable demand for compute. More data plus more compute equals better performance — the scaling laws have led to exponential growth in both training and inference requirements. Now projections of consumer and enterprise AI compute demand far outstrips any reasonable extrapolation of datacenter deployment.

The numbers are staggering. OpenRouter reported over 7 trillion tokens processed in November 2025, up from 350 billion the prior November—a 20x increase in one year. In 2026, inference is projected to consume more compute than training for the first time. And bleeding-edge reasoning models employ significant “test-time compute” that can 10x or more the inference tokens required for a single query.

All of this compute needs power. Total US datacenter consumption in 2025 likely exceeded 40GW. Projections vary, but many estimates predict cumulative need of 100GW of new capacity by 2030.

Like Indiana Jones sprinting for daylight ahead of a quickly closing cave door, the AI labs have raced to deploy unprecedented datacenter capacity before the resource window closes. And the realization that this crunch is coming, and fast, has led everyone involved to think creatively about ways out.

The Case for Space

There are obvious reasons hyperscalers are looking to space. Space provides practically limitless solar energy, 40% more intense than on Earth. More importantly, with appropriately selected orbits this energy is always on — baseload power that doesn’t require backstops like battery storage terrestrial solar does. A watt of solar deployed to space is 5–10x more valuable than the same on Earth.

Space is also an excellent heat sink. Deep space presents a near-absolute-zero background that warm objects can radiate energy into.

And space is remarkably unregulated — no grid interconnection process, no permitting, no water rights, no NIMBYs.

Less well covered are other factors that, I believe, make space-based infrastructure inevitable regardless of the AI compute crunch.

Security and resilience. Infrastructure in orbit has a fundamentally different security profile than infrastructure on Earth. Physical access is nearly impossible. Optical inter-satellite links are extremely difficult to tap covertly. And the innate geometry of constellation orbits makes networks mesh-like and thus harder to disrupt than point-to-point terrestrial networks constrained by terrain, oceans, and jurisdictional boundaries.

Data gravity. As more services, sensors, and systems deploy to space, the bottlenecks in moving data through narrow, intermittent links to ground stations become more problematic. If the goal is to “close the loop” on orbital systems, it will quickly make far more sense to keep (and move) the data in space and process it there. The data wants to stay where it’s generated.

Geopolitical sovereignty. The space regulatory environment is both less developed and inherently detached from local jurisdictions. If you are a multinational technology company or a sovereign nation concerned about global reach under a rapidly shifting international order, infrastructure that transcends terrestrial boundaries becomes strategically attractive.

Combined with The Flywheel, it is not hard to see why people are excited about ODCs.

Below the Waterline

Like the tip of an iceberg, the focus on ODCs distracts from something much larger hiding below the surface — a structural revolution in technology.

Economist Carlota Perez argues that technology revolutions share two defining characteristics:

- strong interconnectedness among participating systems, and

- the capacity to transform profoundly the rest of the economy and society.

Both of Perez’s defining characteristics are now materializing in the convergence of space and terrestrial technology. Let me take them in turn.

Interconnectedness

We rely on space-based technology in our daily lives and often don’t realize it. Our devices listen to navigation signals from GPS, Galileo, and BeiDou. The weather forecasts we rely on to plan our day are entirely dependent on remote sensing satellites. Many of us depend on satellite services for TV or internet, especially outside metro areas. Vast swaths of industry rely on satellite communications for asset tracking and remote monitoring. The US military is critically dependent on powerful (but outdated) satellites to project power around the globe.

Important as they are, these systems have historically lived on isolated islands — largely decoupled from the broader technology ecosystem. Like the mainframes and minicomputers of the past, they were built in siloed technological paradigms.

That isolation is ending. The old-fashioned systems that were once independent are becoming deeply coupled with each other and with systems on the ground — creating the web of mutual dependencies that Perez identifies as the hallmark of a revolution.

Starlink, Amazon LEO and the Pentagon’s MILNET system are good examples. Each are standards-based communication networks designed to transparently link internet systems and users on the ground through space.

Apple’s Emergency SOS via satellite and the race for other “Direct-to-Device” satellite service are quietly plugging space communications infrastructure into the consumer technology stack. Every smartphone is becoming a satellite terminal.

This is the structural pattern of major infrastructure installation, and it extends well beyond SpaceX.

Transformation Potential

The second of Perez’s criteria asks whether the technology can reshape industries far beyond its origin. Here we also have a lot of supporting data.

Global agriculture is shifting from regional, sampled monitoring to continuous planetary-scale observation — satellite imagery combined with AI enables precision farming at a scope that was physically impossible a decade ago. Financial markets are being repriced by real-time overhead imagery of supply chains, ports, and commodity stockpiles. Parametric insurance products triggered by satellite-observed events are replacing slow, claims-based models.

The FireSat constellation is transforming wildfire management, utility risk, insurance and the public’s situational awareness during a threatening fire.

Global carbon monitoring systems like MethaneSat, CarbonMapper and GHGSat are creating entirely new compliance and trading frameworks.

These and other examples address food security, finance, energy, land, natural resources, national security and more. The reach and impact of applications in space is exploding before our eyes.

Convergence & Scale

What’s happening now mirrors the emergence of broadband internet and the paradigm shift to ubiquitous connectivity, large-scale cloud compute, and proliferation of smart edge devices. We are in the early stages of a systematic unification of all technology infrastructure on Earth and in space.

Orbital datacenters are not some singular revolution on their own. They are a natural product of this convergence.

Space infrastructure will mirror and merge with terrestrial: large-scale, multi-layered networking, compute, and storage in orbit powering a “smart edge” of thousands of autonomous sensing satellites with always-on connectivity to orbital infrastructure. The distinction between space and Earth will dissolve entirely. What remains is just global infrastructure — optimized across whatever domain is most efficient for a given function.

Accelerant — Aligned Incentives

There are many aligned incentives pointing towards big bets on ODCs — some of them obvious, some less so.

Launch providers (beyond just SpaceX) are investing billions toward building rocket fleets with massive, reusable launch capacity. They need demand to justify the investment, just as SpaceX did with Falcon 9. Proliferated constellations and ODCs represent the kind of high-volume, sustained demand that makes reusable launch economics work. Tapping into the hundreds of billions in CapEx flowing into AI datacenters would be a massive windfall. They are highly motivated to make this real.

Space systems manufacturers see a vast potential market beyond anything that has existed. AI created a massive new market for Nvidia beyond traditional graphics and supercharged them into the world’s most valuable company. The same dynamic could propel space technology companies far beyond niche commercial and government markets.

Hyperscalers face a problem that is both narrative and real: projected demand for AI compute far outstrips reasonable projections for terrestrial infrastructure deployment. “Space solves our constraints” is a compelling story — perhaps too compelling — which is why it deserves scrutiny. But the incentive to project an “easy button” for scaling is real, and there are billions in capital available to throw at the problem.

Semiconductor and AI foundation model companies see national security markets as a growth area and space as the “third leg” of defense-industrial demand alongside chips and AI. Hitching their products to the newly contested space domain is strategically attractive.

The National Security Driver

Another force is also accelerating this.

The US Department of War is explicitly trying to foster a commercial space ecosystem reminiscent of the 1960s defense-industrial base. The goal: leverage commercial innovation and scale for national security rather than building bespoke government systems.

Space is uniquely important from a national security perspective and space technologies are inherently dual use.

The US cannot project power in the world without a vast array of satellites for communications, intelligence, fire control and more. China has made clear that it sees it as a legitimate war theatre and is likely building significant offensive capabilities in space. It also does not acknowledge separation between military and private/commercial assets in space. This is not an abstract worry or a future projection — China and the US are already playing a game of cold-war prep in space.

The DoW recognizes this openly (as does the PLA). Programs like the Space Development Agency’s proliferated low-Earth orbit architecture represent a fundamental shift from exquisite, vulnerable legacy systems to resilient, distributed, commercially-derived and standards-based systems. The Pentagon is betting that commercial space innovation — built at commercial speed and commercial scale — is the only way to maintain advantage against a near-peer adversary building capacity faster than traditional defense acquisition can respond.

This creates an unusual dynamic and another convergence. In the same way AI chips and foundation model building have become both explosive commercial areas and national security interests, commercial space companies are becoming strategic national assets whether they intended to or not. The line between commercial products and national security capabilities further amplifies the importance of space infrastructure and is powering huge investments in it.

When launch providers, hyperscalers, chip companies, AI labs, and the US government all have aligned incentives, things have the potential to transform quickly.

Timelines & the Bear Case

There are critics of ODC-mania and they shouldn’t be dismissed.

Supply and Demand

The landscape for both supply and demand in terrestrial datacenters could shift dramatically.

Breakthroughs in model architecture are hard to predict but seem to occur every 3–5 years — if newer model architectures require far less compute, the demand for massive datacenter deployment could collapse. Or there could be a fundamental unlock on the supply side. Necessity is the mother of invention and creative site-local power solutions for getting around grid connect constraints are being developed rapidly. Is it easier to innovate our way out of this on Earth or in space?

Engineering Reality

Engineering realities of deploying massive solar arrays and radiators in space are unproven and non-trivial. Moving heat from the AI chips to surfaces that can radiate is a big challenge without air and doing so in a way that is lightweight and cheap enough to launch to space is even harder. The ultra-high-bandwidth interconnect problem is especially hairy for those focused on AI compute workloads — something that Google has acknowledged but most commentators gloss over.

There has been a revolution in launch — but it’s not enough yet. Even with very aggressive estimates for satellite mass and cost, launch costs today are still 5–10x too high to make ODCs cost competitive with terrestrial infrastructure. The interactive launch cost calculator above shows that achieving the required launch costs is possible but requires another order of magnitude in launch cadence beyond what SpaceX has achieved to-date.

The number of satellites in orbit is totally uncharted territory. How will we manage traffic for millions of football-field-sized satellites in orbit? Can we really reliably push enough bandwidth to and from satellites with laser links with all the cloud in the way? What will 10,000 launches per year do to the local environment or the upper atmosphere? What happens to the upper troposphere as all those satellites re-enter?

These are serious objections. With Starship still in development and no obvious million-satellite factory running, Elon’s claim that space will be the cheapest place to deploy datacenters in 3 years is not realistic.

Exuberance

There’s also a less charitable read to the incentive alignments point.

Perez observed that every technology revolution follows a pattern: an installation period driven by financial capital — speculative, frothy, often producing bubbles — followed by a deployment period where the technology matures into productive infrastructure. The telecom bubble of the late 1990s laid the fiber that made the modern internet possible. The railway manias of the 19th century left behind the rail networks that industrialized continents. In each case transformation followed a period of investment and wild speculation.

Many of the same investors with large AI portfolio positions also have significant space investments. The ODC narrative conveniently supports both. When the same capital has exposure to both the “problem” and a “solution,” some self-dealing should be expected.

This doesn’t mean ODCs won’t happen — but it does mean the hype cycle may run ahead of reality and there may be some big bumps along the way.

Implications

If the convergence described above plays out — and the structural forces suggest it will — several implications follow.

The boundary between space and ground dissolves. Most people and organizations won’t know or care whether their data is processed on the ground, in orbit, or split across both. Latency, cost, availability, and regulatory constraints will determine routing — not domain. The “Cloud” will literally extend into space. The distinction between “space infrastructure” and “terrestrial infrastructure” will become as meaningless as the distinction between “wired internet” and “wireless internet” is today.

Every technology company becomes a space company. If your connectivity, your data sources and networks, your compute, or your supply chain visibility runs through orbit — and increasingly all of them will — then you have a space dependency whether you chose one or not. Just as companies in the 1990s scrambled to build an “Internet Strategy”, every company in the 2030s will need a “Space Strategy”.

A Cambrian-explosion of space-native technology companies will emerge. Built more like software companies than aerospace primes, they will unlock trillions in value building the applications, platforms, and services that sit on top of large scale infrastructure. Outdated bespoke, government-funded space systems will be replaced en-masse over the next decade by technology that shares a lot more with consumer products and datacenters than those traditional systems.

Expanding critical infrastructure into space increases capability and resilience — but also creates new categories of risk. On one hand, redundancy between space and ground makes systems harder to disrupt. Geographic decoupling reduces the vulnerability of concentrated terrestrial facilities. Systems like FireSat will improve public safety and make our forests healthier.

On the other hand, infrastructure that entire economies depend on now operates in a domain that no single nation controls, that is increasingly contested, and where the rules of engagement remain undefined. Space is now a contested domain and is considered by China, Russia and the US a theatre of war. A major orbital event — deliberate or accidental — could cascade across the global economy in ways we have never experienced and are not prepared for.

Conclusion

ODCs will happen. The incentives are aligned from too many directions for them not to. But if you’re still debating whether datacenters in space “make sense,” you’ve missed the point.

The real story is a technology revolution hiding in plain sight. Access to space has transformed over the last decade. Space and terrestrial infrastructure are converging into a single global system. The installation period is underway — speculative, messy, and already building the foundation for what comes next. Whether any particular infrastructure bet succeeds in the near term matters far less than the fact that the underlying transformation is structural and self-reinforcing.

Twenty years ago I sat in a Texas blockhouse watching a rocket startup’s first engine tear itself apart unceremoniously moments after ignition. The company that built it now operates launch like commercial airlines and is poised for a $1.5T IPO.

The revolution doesn’t announce itself cleanly.

Appendix A — Launch Economics

Rocket science is hard, but rocket economics might be even harder. To understand why launch prices are dropping — and where they might go next — we have to look beyond the fuel and metal and into the math of production rates and reusability.

Below is a breakdown of a simple economic model for launch vehicles, followed by an interactive calculator where you can test the assumptions yourself.

The Model

The specific cost of a launch is the Total Loaded Cost divided by the Payload Mass:

Total cost is composed of two buckets — Fixed Costs and Recurring Costs:

Fixed Costs (The “Standing Army”)

Fixed costs are the expenses you pay whether you launch a rocket or not — engineering teams, launch pad leases, manufacturing infrastructure. The cost per launch is the total annual fixed cost divided by launches per year ():

If you have a massive team but a low flight rate, your fixed costs per launch skyrocket. High flight cadence is critical.

Recurring Costs (Hardware & Ops)

These are the costs directly attributable to a specific mission:

- — launch operations (range fees, recovery teams), modeled as a fixed cost per mission.

- — propellant and fluids, a function of vehicle size and payload.

- — vehicle hardware manufacturing cost

Consumables are proportional to payload so that

A high quality analysis of consumables would model things like the payload mass fraction as a function of cost/complexity/rocket scale. For our purposes, we will substantially simplify this to use a simple fixed payload mass fraction and fixed structural mass fraction based on type of reusability where:

and

Finally then the propellant mass is

And finally we need a cost / kg for propellant, ($/kg). The various constants for each of the scenario types are captured in the table below -

| Scenario | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Use | 0.05 | 0.04 | $0.90 / kg |

| Partial Reuse | 0.03 | 0.05 | $0.90 / kg |

| Full Reuse | 0.02 | 0.06 | $0.33 / kg |

The Learning Curve (Wright’s Law)

Hardware costs are not static. As you build more rockets, you get more efficient — Wright’s Law, “The Learning Curve” or “The Experience Curve”. Cost decreases by a constant percentage (the learning slope ) for every doubling of cumulative production.

We assume a baseline build rate of 10 vehicles per year. Hardware cost scales based on annual production rate relative to that baseline:

Reusability

Reusability changes the production volume equation drastically:

- Fully Reusable: Reuse a rocket times and you only build per year, amortizing build cost over flights.

- Partial Reuse (e.g., Falcon 9): The upper stage is single-use (high production volume); the booster is reusable (lower volume, amortized).

So

and

where is the fraction of the overall hardware cost that the reusable 1st stage represents. This is adjustable via the “1st Stage Cost Fraction” slider in the calculator (default 50%).